The Nature of the Universe

- Dec 25, 2015

- 3 min read

There has been an ongoing philosophical debate over how to view the universe. It is a constant challenge on which conceptual worldview will help to answer this question. In Oelschlaeger’s Wild Nature, he states “The differences between these two worldviews—mechanism and organicism—are important,” (Oelschlaeger, 1991, “Wild Nature,” p. 129). Hargrove also identifies great thinkers of organismic inclination, by carefully examining each concept in “Philosophical Attitudes.” The mechanism of nature is considered the modernistic view point, and the organismic view of nature is the critic to modernists. Could there be only one view point to envisage the universe? The answer lies within the many different thinkers and outcomes of their examinations.

During the Scientific Revolution, key thinkers of modernism changed the very meaning of the term nature. Galileo created a new science, Bacon streamed new logic, Descartes was a mechanistic reductionist, and Newton advanced physics (Oelshlaeger, 1991, “Wild Nature,” p.76). Without all of these thinkers, modernism would not be what it is today. These observers narrowed and thoroughly looked upon the universe without primary judgement. What you calculate is what you get. Primary judgements are identified by these scientists as the senses. Modern scientists ceased sensory observations of nature such as color, sight, sound and taste replaced the “world devoid of secondary qualities,” (p.77).

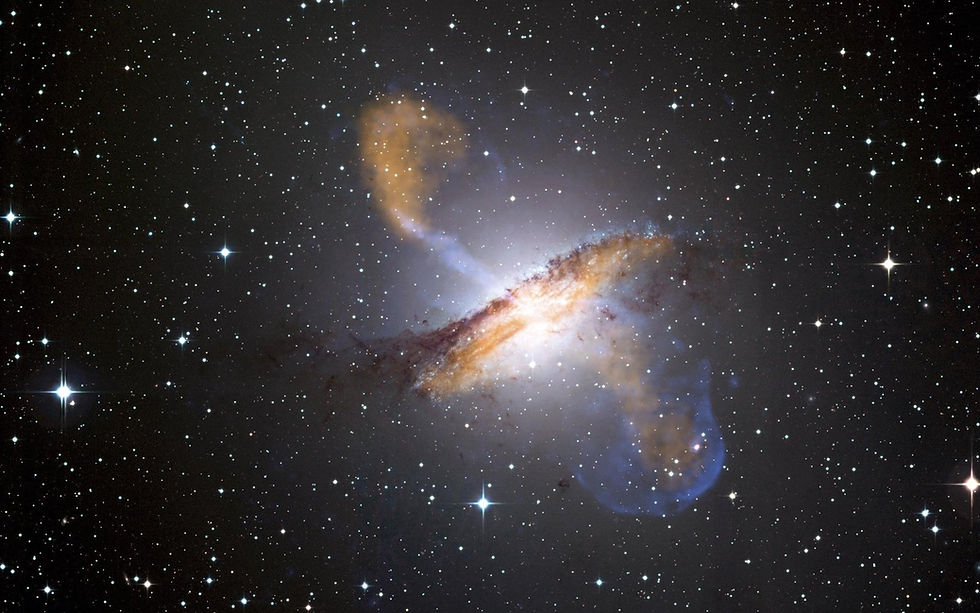

Galileo was the source of the shift from organismic to mechanistic by his use of the telescope, collecting accurate data and standing outside of nature to observe it rather than within. This “causal explanation” of the universe completely shifted the belief of random chaos to mathematical precision as identified by Descartes (Oelshlaeger, p. 88). Another mechanistic thinker, Isaac Newton identified, the systems of the world as an understood mechanical repetition which is predictable and determinate (p.90). This birthed some of the theories of creation of the cosmos. If nature is predictable, than the universe is not an entity to communicate with, but a nonliving unintelligent and predictable machine.

Hargrove does not believe that science as a whole is anti-environmental. He claims “The most positive influence on the environment came out of sciences that did not fit the preferred model of what science should be…” (Hargrove, 1989, Philosophical Attitudes, p.40). The scientists which believed in a holistic view point, such as Aristotle, looked at the impact of the entire picture without constricted objectivity. For example, Charles Darwin was a great thinker whom associated science with the invisible world of his own senses; seeing and feeling. Without his senses stimulated, his mind stagnated (p.42). So he incorporated art and imagination into his work. Thus, his imaginary thinking was what gave way to the theory of human evolution. Rather than dissecting the natural world and detailing narrowed observations, he saw the connection of lizards to birds, apes to hominids and more. Consequently the natural world as seen through Darwin’s eyes was due to the perspective from his aesthetic inclination (p.43). Accordingly, scientists with a Darwinian outlook may connect the microcosm of a brain cell to the macrocosm to the universe. This may lead to a theory of creation stating the universe is a mere thought in a cosmic brain cell.

Critics of modernists are observing the observers whom detached themselves from nature. In order to compile a correct perspective of the universe it is important to understand both sides. The debate of primary and secondary or what ought to be compared to what is, as a vice and virtue of perceptions continues. Thus Oelshlaeger was correct to say “Modernism is no one thing but a collective process greater than the sum of its parts,” (Oelshlaeger, "Wild Nature," pp. 128-132). Yet the paradox remains, and the answer to find the “right” view of the universe may be found in subjective science, objective or both?

References

Hargrove, E. C. (1989). Philosophical Attitudes. In Foundations of Environmental Ethics (pp. 14-47). Denton, TX: Environmental Ethics Books.

Oelschlaeger, M. (1991). The idea of wilderness: From prehistory to the Age of Ecology. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press

Comments